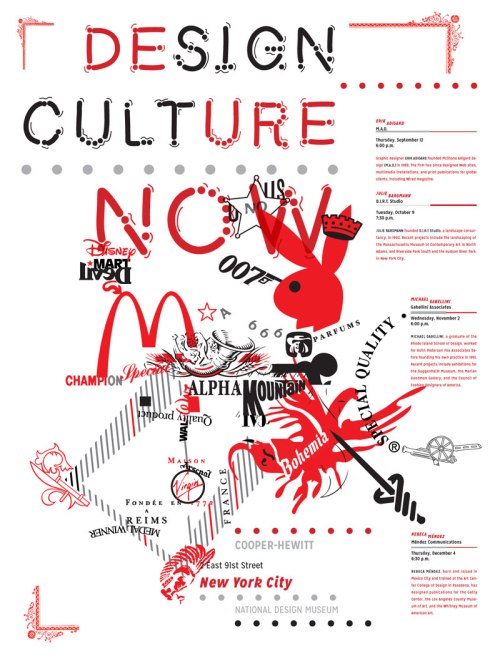

Visual Essay

Definition

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Essay

What Does Creating a Visual Essay Imply?

To begin with, a visual essay appears to stand out of the crowd. Actually, it is a totally different assignment from a classic essay. The point is that while covering this written task, you shouldn’t write anything at all except for some short informative statements!

In fact, this academic assignment requires expressing your thoughts on this or that topic using:

- Pictures

- Images

- Visuals

Moreover, to present your point of view on the required topic you may combine all above-mentioned means with some short informative statements related to the theme.

Handling Visual Assignments

Clearly, the most difficult and challenging step while fulfilling this task is finding really suitable and gripping visuals, pictures and images to use. Obviously, it presumes using creative approach and skills. In other words, ability to generate fresh ideas seems to be a determinant factor on your road to success.

Recommendations on Composing a Visual Essay

Are there any clear effective hints, which can help you to create your visual paper with ease? Of course, there are! And you shouldn’t seek for them, because they are posted below:

- Surf the web and use camera to collect the data for your essay.

- Incorporate thought provoking visuals, images and pictures in your paper.

- To make your presentation more griping feel free to use graphs, various charts and bars.

- All the data you want to use should be up-to-date and relevant.

- Don’t forget about numerous visuals aids while defending your paper.

- Show your paper to your relatives of friends before submitting it. They may give you favorable advice as well.

Competent Help with Visual Essays

Still feel a little bit frustrated because of these academic assignments? Don’t fall into despair! There is always a way out from any tough situation! Visual papers are not an exception.

::

http://writingbee.com/blog/essay-writing/how-to-create-a-visual-essay

• • •

How to Write a Visual Essay

By Marlene Inglis, eHow Contributor

Visual essays tell a story either by using text or props.

A visual essay can be a group of pictures depicting or exploring a topic without any text or it can be a combination of visuals or images plus text. Your essay can be a commentary on ideas ranging from gardening to social uprisings and can focus on political or environmental issues. Pictures used in your essay can be current pictures or ones collected over a period of time and the essay can be presented either as a word document or as a .jpeg image file format with some accompanying text.

Instructions

- Create your visual essay by deciding which format you will be using for your essay. Remember that the purpose of your essay is to inform, persuade or enlighten your reader. Create an essay that is factual but not boring, lots of images or pictures but not enough to overwhelm, thought provoking but not thoughtless.

- Use charts, bars or graphs to tell your story. Select a subject such as statistical processing control (SPC), a process used in the manufacturing industry to monitor product quality, and create graphic charts, bars and graphs. Use vivid colors in your presentation so your audience can observe and compare the variations in manufacturing the product over certain times of the year. Create comparative charts and graphs to show the current year’s product quality compared to previous years. Using the appropriate visuals for your subject matter is paramount in keeping your audience interested and informed.

- Write your essay on a topic such as “uprisings” and use current pictures or images of an uprising in a country. Collect dozens of pictures pertinent to your subject matter and save them in a .jpeg format. Select pictures that can tell your story such as individuals looting and hauling store merchandise across their backs, people of all ages being unceremoniously dragged across roads, tanks lumbering through city streets while people run for cover and cars and buildings ablaze. Accompany the pictures with suitable background music and your visual essay would not need much text since the pictures by themselves will speak to your audience.

- Use visual aids or props. Purchase various fast foods such as hamburgers, fries, nachos, coke, etc. for your essay on “The obesity epidemic”. Research the fat content, the amount of sugar, salt and other ingredients contained in each food item. Prepare a power point presentation with text to accompany your visual essay and include information on the normal amount of fat, salt, sugar etc. each body requires per day compared to the amount that these items provide. Include some pictures of people in various body sizes. Your presentation should be informative but not preachy. Let your audience make their own decision.

• • •

How to Write a Picture Analysis Essay

By Tom Becker, eHow Contributor

A picture is always more than the sum of its parts.

Art moves us. Whether it makes us feel joy, sorrow or revulsion, art has the power to affect us and express ideas that transcend rational thought and language. Art communicates these primal experiences not just through an artist’s inspiration, but also through very clear, recognizable visual communication techniques. Writing a picture analysis essay requires a basic understanding of essay structure and these visual communication techniques. Excellent picture analysis essays combine both these elements while addressing the more ephemeral ideas and experiences communicated by a picture.

Instructions

Analysis

- Note how the picture makes you feel. Do this before you make any intellectual analysis of the picture. Immediate, unprepared and unguarded observation will often tell you more about the content communicated by the painting than rigorous analysis.

- Address the age of the picture. Take note of the period from which it comes, what styles dominated that era, what techniques artists used and who commissioned the work. Consider the current events going on at the time of the picture’s creation and what social or cultural elements or changes may have affected its content.

- Find out the dimensions of the picture. A large picture communicates very differently from a small one. Generate reasons why the picture communicates well or poorly due to its size.

- Look for the composition of the picture. Composition refers to the way the elements are oriented in relationship to one another. Observe if the objects seem crowded or sparse, symmetrical or asymmetrical. Consider why the objects in the picture have their specific orientation.

- Take note of how the picture is cropped. Cropping refers to images that only partially appear in the picture, as if someone “cropped” them out of the picture. Address how cropping focuses the viewer on certain aspects of the picture and what ideas the cropping may help communicate.

- Observe the levels of light in the picture. Take note of the visible and obscured objects and where the picture draws the viewer’s eye. Think of the role light and darkness play in communicating feelings or ideas in the picture.

- Look for color. Observe the way the picture utilizes color or lack of color. Address the effect different colors in the painting have on the ideas it communicates.

- Observe the form of the images in the picture. Whether an image has clearly defined lines and boundaries representing a real object, or has no defined shape can communicate very different ideas and emotions. Address the reasons why the image has or does not have a clearly defined shape.

- Look for texture. Pictures with completely flat surfaces may communicate differently than pictures with highly textured surfaces. Address how the texture or lack of texture conveys ideas and emotions in the picture.

- Take note of your gut reaction to the painting after your thorough analysis. Address how the various elements came together to help form your initial impressions and how analysis either strengthened or weakened your initial impressions.

Essay Structure

- Choose a thesis. A thesis represents the main idea of your essay, the point you wish to communicate. Use your thorough analysis of the picture to make a list of opinions you wish to assert about the picture. Choose the strongest idea that most clearly communicates and unifies your assertions as your thesis.

- Introduce the first assertion of your essay with a topic sentence stating that assertion.

- Develop the assertion in the next few paragraphs by citing specific examples that back up your assertion.

- Conclude each assertion by restating the assertion and briefly summarizing the manner in which you have proved your assertion.

- Introduce your next assertion with a topic sentence and continue in this fashion until you have made all the assertions backing up your thesis.

- Conclude the essay with a restatement of your thesis statement, briefly restate your assertions and finish with a sentence or two stating what you have proved with the essay.

::

Read more: How to Write a Picture Analysis Essay | eHow.com http://www.ehow.com/how_7902271_write-picture-analysis-essay.html#ixzz2DdhmflLW

• • •

How to Start a Reflection Essay on Art

By Isaiah David, eHow Contributor

Because a reflection essay on art is your chance to go back and take an informal look at a substantial project you have completed, many people incorrectly assume that it will be the easiest part. In reality, it takes a mature perspective, a developed voice, and the ability to be simultaneously informal and articulate to write a good reflection essay on art. In this article, I assume that you are writing a reflective essay on art you have made yourself, but the instructions can be easily adapted to help you reflect on an art history unit or a report you did on an art exhibit.

Instructions

- Consult the rubric. Generally, your teacher will provide a list of points you are expected to address. Jot down a few notes on each point. Don’t try to be comprehensive – keep it light and flowing at this stage. Think of the first things that come to your mind.

- Look at your art project. What does it make you think about? Do you like it? Hate it? Take a closer look at the details. Was there some part that you had to struggle to complete? Was there something that came easy or hit like a burst of inspiration? Write down as much or as little as you are inspired to.

- Think about the project as a whole. Find a moment that encapsulated the whole process of creating, refining, and finishing your work of art. It could be the first moment where you really felt engaged in the project, or it could be an obstacle that nearly stopped you dead in your tracks and that you had to overcome. That is where you should start your reflective essay.

- Use the drama of the moment you just thought of to begin your essay. You want your essay as a whole to tell the story of your project, and your first paragraph to tell a story within that story to draw the reader in. Use vivid descriptive to make the reader feel what you felt.

- Leave the reader hanging. Don’t tell the whole story of whatever moment you chose in your introductory paragraph – leave something for the ending. Then, you can keep the reader interested in the story within the story even as you lead them through the entire process.

- Step back to tell the rest of the story. For example, if you start with a description of a last minute problem you had to solve in your art project, you might start the next paragraph with something like “By that point, of course, I had been working on the project for 6 weeks.” This will take you right back to the beginning of the project, allowing you to reflect on each stage in order.

- 7 As you go through, use the details you thought about in step 2. If there are some aspects of your work that you are especially proud of, tell the reader how they came about. If there are other aspects that you don’t like, tell the reader why you don’t like them. Don’t just list them, but put them in at whatever stage of your project they occurred.

- Make sure to hit every detail on the rubric. Try to keep it in the back of your mind as you go through. Tat way, you can integrate it into the flow of your essay and make it sound more natural.

- For your conclusion, come back to the mini story and relate it to the project as a whole. If you found you had to trust your intuition to complete one aspect of your piece, explain what the project as a whole has taught you about intuition in art. If you had to scrap it all and start over at some stressful point, you might talk about what you learned about the need to plan, or the willingness to admit to yourself when you are wrong. Be humble. Show that there is something you had to learned, and that you learned it.

::

Read more: How to Start a Reflection Essay on Art | eHow.com http://www.ehow.com/how_4424616_start-reflection-essay-art.html#ixzz2DdmgOaj6

• • •

How to Write an Art Essay

By Melanie Novak, eHow Contributor

Writing an essay about a piece of art is best approached by considering two things:

- What did the artist set out to accomplish?

- How well did that artist achieve her goal?

This criterion is useful in a few ways. It’s relatively fair (you won’t be holding the work to unrealistic standards), it clearly sets up the basis for your critique, and looking at a work this way avoids a thumbs-up or thumbs-down review. You can use this approach to write about a book, movie, theatrical performance, painting, piece of music or any other creative work. The bulk of the work of writing about art is actually the time it takes to analyze the work and write the outline. There are some challenging steps in the first parts of this how-to, but if you have a strong, solid outline, the writing will be easy.

Instructions

Analyzing the work

- Write what you think the artist was trying to achieve with this work of art. The famous Mona Lisa, painted by Leonardo da Vinci in the 16th century, is a notoriously inscrutable painting. You cannot, obviously, know exactly what da Vinci intended by painting this portrait. Many accomplished art historians have written extensively about this painting. So what can there be for you to say? Plenty. In this example, an essay on the well-known painting the Mona Lisa, you might conclude that the artist was trying to paint a portrait that told a story about a particular woman. This may seem obvious, but remember that goal is quite different from, say, an instructional painting with an obvious religious allegory or an abstract modern painting, and so the evaluation of this particular work will accordingly be different.

- Write what you know or feel as a result of the creative work. For instance, what do you know about the woman from looking at how she was painted by da Vinci? These needn’t be facts about her identity, but rather impressions that you have of her. Be as honest and specific about your reactions as you can. Do not worry about your own authority. You don’t need to be a professional art critic or have painted an Italian masterpiece yourself to be able to write an effective essay about the Mona Lisa.

- Compare your answer in Step 2 to the artist’s goal in Step 1. Is your reaction what the artist intended—is the work of art successful? Remember that it doesn’t matter whether or not you “like” whatever you are writing about. Rather you are using your own responses to write an analysis of the work itself. Remember that you can write an essay that examines how the work was unsuccessful using the same method as when writing an essay on a successful work.

- List the variables—all the decisions the artist or artists had to make—that went into creating the work. In the example of the Mona Lisa, the variables would be subject, composition, materials (paint and surface), color palette, brush strokes and level of detail.

- Write next to each variable a short description. For instance, for the Mona Lisa, you would write “subject–woman,” “composition–close-up of face, centered in the frame,” “color palette–muted,” etc.

The thesis statement and finalizing the outline

- Write a rough thesis statement based on all the steps above. Don’t use first person, even though your own responses have informed your thinking so far. A rough thesis statement might be “Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa is a visually beautiful painting using Renaissance painting techniques, but its subject remains mysterious.” Your thesis statement should not be “The Mona Lisa is good.”

- Organize the variables in a way that supports your thesis statement. You don’t need to include every variable you listed. You may want to write one paragraph for each variable.

- Note how each variable contributed to the overall success (or lack of success) of the creative work.

Writing the essay

- Write as specifically as possible when you are describing the variables and your responses to them. It is often the description that will convince your readers of your point.

- Write an engaging introduction and satisfying conclusion.

::

Read more: How to Write an Art Essay | eHow.com http://www.ehow.com/how_5137598_write-art-essay.html#ixzz2DdlSnkCh

• • •

The Visual Essay— collated research material